Educators Have the Power to Change Outcomes for Students

Recently the New York Times published an editorial called “The Common Core Costs Billions and Hurts Students”. In it the author argues: “What we need are schools where all children have the same chance to learn. That doesn’t require national standards or national tests, which improve neither teaching nor learning, and do nothing to help poor children at racially segregated schools.”

We do not agree.

In response, Green Dot Public Schools Board Chair, Marlene Canter, and Board Member Gov. Roy R. Romer offer their thoughts. Canter is a former Board Member of LA Unified School District (2001-2006) and a former Board President of LA Unified School District (2005-2007). Romer served as the Governor of Colorado (1987-1999) and is a former Superintendent of LA Unified School District (2001-2006). Both are long standing participants in this public policy dialogue.

In her attempt to take down our nation’s first national educational standards, Diane Ravitch dismisses accountability and the national testing on which it is based. These tests, she claims, are “best at measuring family income” rather than the dynamics that happen between teachers and their students.

And yet, her argument against Common Core is based largely on those same tests. She grades the standards’ early results on the math and reading scores on last year’s – and just last year’s – National Assessment of Educational Progress and tries to declare a downward trend has started: “Last year, average math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress declined for the first time since 1990; reading scores were flat or decreased compared with a decade earlier.”

So are the test results valid or not?

If they are, schools and teachers surely bear some responsibility for their students’ outcomes. If they aren’t, then her argument has no basis. Ravitch can’t have it both ways.

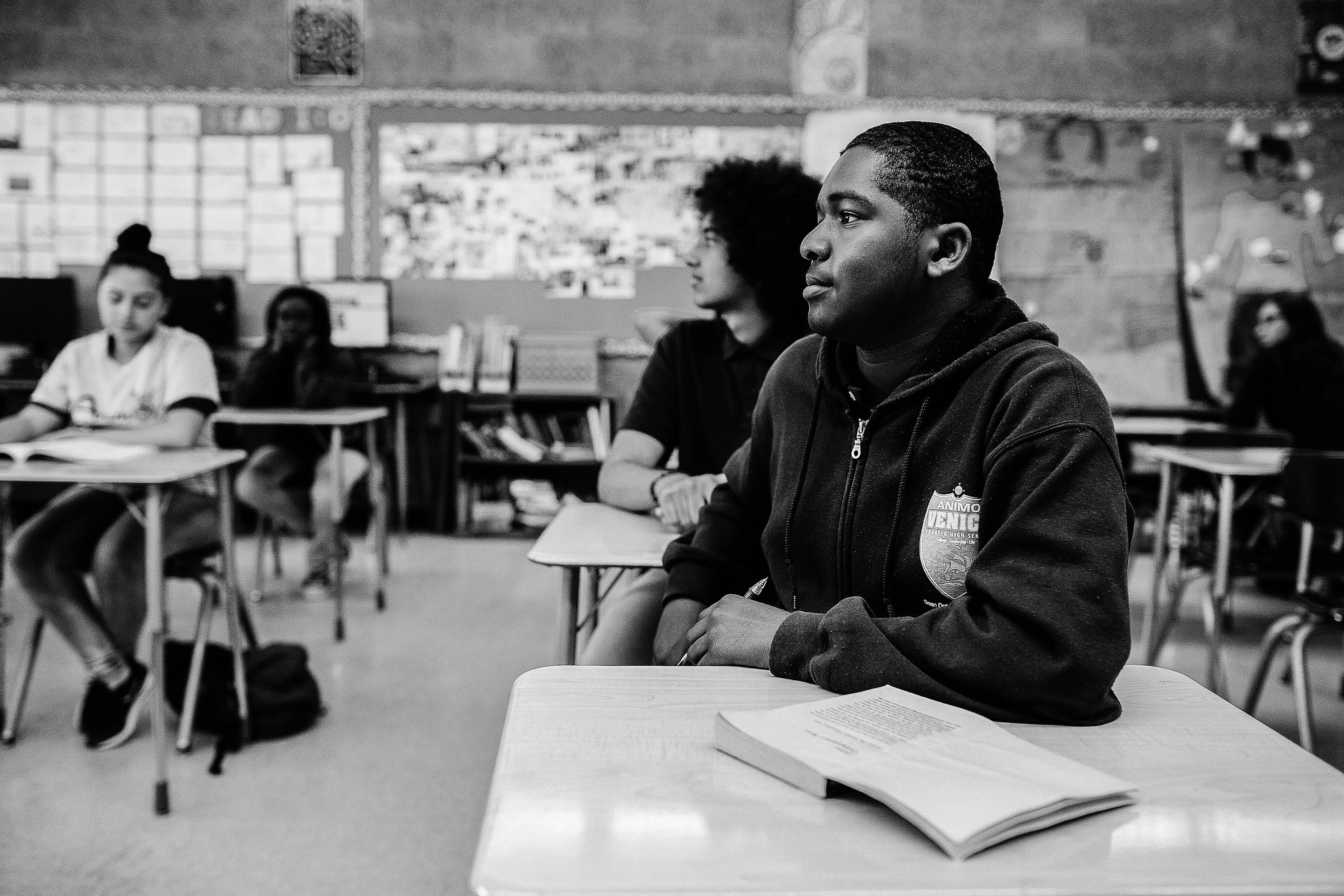

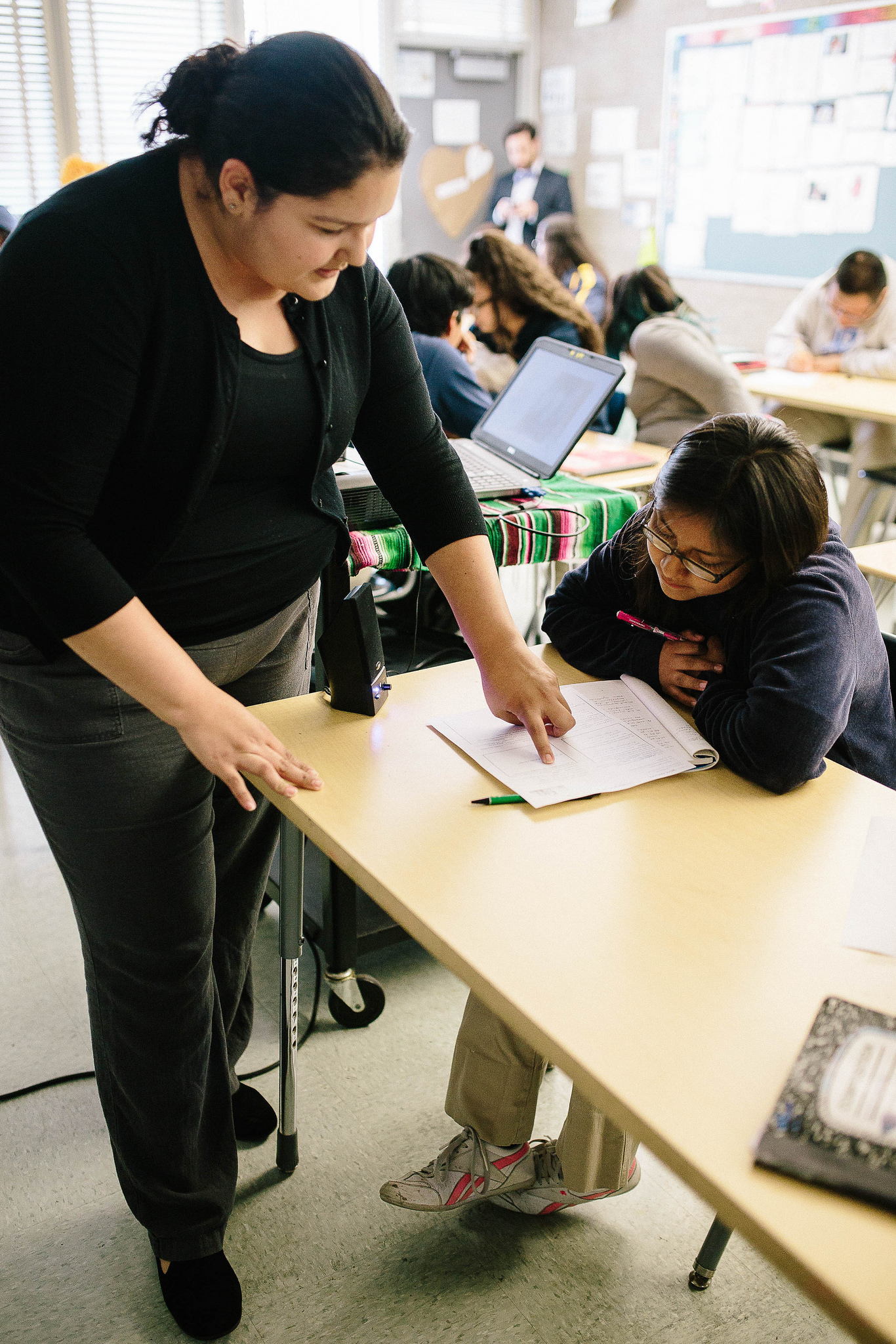

Ravitch insists that tests only measure income and that schools are powerless to change that, yet fails to explain why so many schools in low income communities dramatically change the odds for their students, while others chronically underserve them.

Surely, she must believe that educators must have some power to change outcomes for their students?

And that is unfortunate, because as a nation we need to be having meaningful discussions about our public schools and the fact that too many persistently struggling schools are located in predominantly low-income areas or communities of color.

Content standards offer us a common set of measurements upon which we can have this discussion and begin to find lasting solutions – ones that focus on the ongoing inequities that exist both on and off our public school campuses.